China’s revised regulation on human genome editing: the good news and the bad news

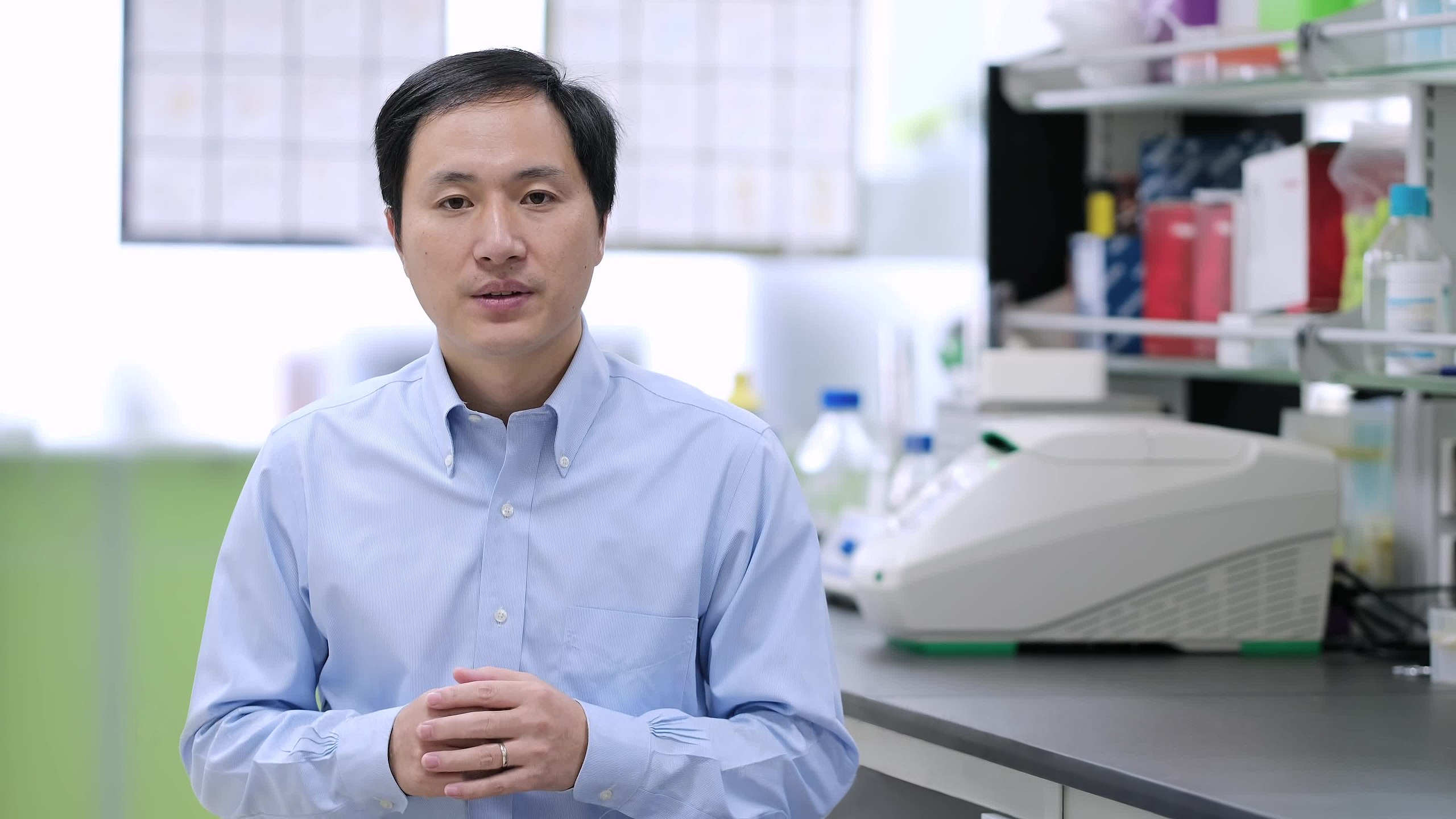

Remember the scandalous revelation of the world’s first births of genome-modified twins (Lulu and Nana) by Dr He Jiankui in 2018? Recently, China revised its regulation on human genome editing. While this is undoubtedly a positive development, there are ambiguities and various concerns.

In Dr He’s experiment, the girls had their genomes modified by CRISPR-Cas/9 to confer resistance to HIV, the virus that causes AIDS. Then, using in vitro fertilisation (IVF) to create the embryos, they were genetically changed by disabling the CCR5 gene (the gene makes a receptor that allows HIV to enter and infect cells) during the single-cell stage.

Scientists are studying this technology, editing mutating genes that cause heritable diseases such as cystic fibrosis, thalassemia, sickle cell anaemia and Tay-Sachs disease. This is indeed a promising technology. But there are also several issues associated with this innovative technology, including the unintended consequences of using this technology on human.

Moreover, heritable genome editing is not yet ready to be tried safely and effectively in humans. Thus, it is vital that this practice can only continue where there is a favourable balance of benefits and risks.

In March 2023, the Third International Summit on Human Genome Editing was held in London, UK, to examine scientific developments, challenges and opportunities in research, regulation and equitable access to human genome editing techniques and procedures. Updates on China’s regulations following Dr He’s controversial experiment was presented by Dr Yoajin Peng from the Chinese Academy of Sciences on the first day of the summit. The newly published revised regulation, Measures for the Ethical Review of Life Science and Medical Research Involving Humans (the 2023 Measures), covers research institutions, including work on human tissues, organs and embryonic cells.

Overall, these substantial amendments in the 2023 Measures are primarily favourable. Life science research is now much more likely to undergo ethics reviews. In addition, the scope of regulated activities is broadened, including studies involving human cells, tissues, organs, fertilised eggs, embryos, foetus and health records.

Moreover, the 2023 Measures list inactions and wrongdoings subject to sanctions, e.g. fabrication of an ethics review. Scientists are penalised if they do not report their research progress to the ethics committee.

Article 36 makes provisions for informed consent by the participants, including detailed information on the matters which should be included in the informed consent process. This is critical as participants must be provided sufficient information before consenting to participate. Finally, article 39 ensures that the ethics committees are adequately funded, well-resourced and regular ethics workshops provided to scientists, administrators and students.

It is also true that the Chinese government acted swiftly to address the regulatory gaps relatively soon after Dr He’s shocking announcement. Within months after Dr He’s announcement, China’s National Health Commission revised its 2016 Measures on the Ethical Reviews of Biomedical Research Involving Humans. Further, Dr He was sentenced to prison and also fined for committing “illegal medical practices“. The Shenzhen Nanshan District People’s Court sentenced him to three years in jail and imposed a 3 million yuan (US$430,000) fine.

However, the other speaker at the summit, Dr Joy Zhang of the Centre of Global Science and Epistemic Justice at the University of Kent, was concerned that the revised regulation does not affect private groups. She explained that: “the ability to collect and access health data and bioinformation extend beyond academia and is exercised by social and private ventures.”

Moreover, the 2023 Measures have a broad description of ethics review exemptions.

Currently, research activities that fulfil the exemption criteria are in hospitals, universities and research institutes, as they have strict codes of conduct. However, scientific practice expands beyond traditional research institutions and the concern is that these exemptions may create regulatory loopholes.

According to Professor Leigh Turner of the University of California, Irvine’s Department of Health, Society, and Behavior:

“Well-defined, carefully crafted regulatory exceptions are often abused and exploited by commercial actors that engage in activities falling outside such narrow exceptions. For financial gain, such entities try to evade regulators and determine what they are able to get away with without suffering significant consequences.”

Finally, while there is a requirement to make a record of research activities in a national database, a mere recording is not synonymous with a registration which requires a thorough review and formal approval of the research project by an ethics committee.

Enforcement has always been an issue in research regulation in China. These challenges include the absence of a transparent regulatory culture and regional and institutional disparities in governing capacity.

Meanwhile, Dr He is now back in the laboratory after serving his prison sentence. He has shifted his attention from embryo edition to gene therapies. He intends to tackle rare diseases such as Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) and opened a new lab. He is actively recruiting DMD patients in his study.

- Utah’s new stem cell law undermines FDA’s authority - April 17, 2024

- Australia’s first human challenge trials centre opens - April 4, 2024

- FDA approves first gene-editing therapy - February 15, 2024