Trans narrative under fire in Sweden

The Swedish national broadcaster SVT has produced a series of programs which are sceptical of transgender medicine. The latest, Transbarnen (The Trans Children), examines the case of “Leo”, a ten-year-old girl who decided that she was really a boy. It is an appalling tale of abysmal medical care – at one of the world best hospitals, the Karolinska.

The troubling revelations from the SVT’s investigative reporters were one factor in new guidelines for gender-affirming care issued in February by the National Board of Health and Welfare. It stated that, based on current knowledge: “the risks of puberty suppressing treatment with GnRH-analogues and gender-affirming hormonal treatment currently outweigh the possible benefits, and that the treatments should be offered only in exceptional cases.”

Here’s what Uppdrag Granskning (Mission Investigation) found.

At the age of 11, Leo embarked upon puberty blockers. The child and her mother were told that this was standard treatment and reversible.

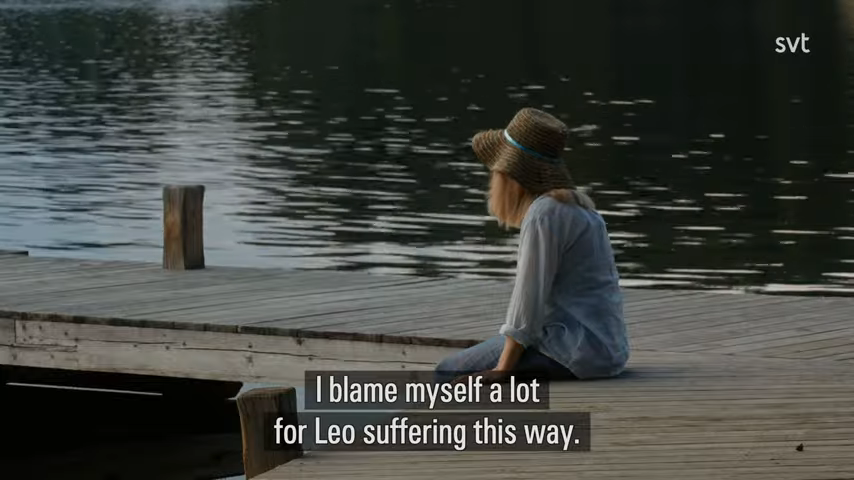

“Leo was little when she wanted to become a he,’ her mother Natalie told the reporter, Carolina Jemsby. “I thought if this was his wish, I should agree with it. Everyone said Leo was brave to come out and I should be proud of him.”

The puberty blockers were meant to stop Leo from developing breasts, wider hips and menstruating. Their use is based on the so-called Dutch Protocol, developed in the Netherlands in 2011. But, as Jemsby points out, some experts have grave misgivings about this repeatedly-cited research. “The worry comes from the lack of long-term studies and that the Dutch study alone is not sufficient evidence. It has too few subjects, no control group and was done at only one clinic.”

Since a well-known side-effect of puberty blockers is a serious decrease in bone density, patients are supposed to be checked regularly. They should receive the powerful drugs for no longer than two years.

Leo was on the medication for four years and his bone density was never checked.

The effects were little short of catastrophic. Leo now suffers from severe osteoporosis, a weaking of bones which is normally seen in people in their 60s and 70s. It is almost irreversible. His mother says that he was in pain from skeletal damage; he was constantly depressed; and he attempted to commit suicide several times.

“But information about the potential risks and lack of evidence never reaches Leo and his family,” says Jemsby.

In fact, one of the most dismaying features of the Swedish journalists’ report is mismanagement in the medical bureaucracy. One group diagnosed children’s gender dysphoria; another administered the medications. They didn’t appear to communicate with each other. Patients were falling through the cracks. If this happens in one of the world’s best hospitals, what happens elsewhere?

Jemsby showed doctors incident reports not only on Leo, but on “at least 12 other children” who had serious complications after embarking upon puberty blockers. The response? Creased brows and pursed lips and finger-pointing and no answers. No one, it appears, was responsible.

“I think everyone involved in this case had good intentions,” Dr Ola Nilsson, a paediatric endocrinologist, tells Jemsby. “But now it’s time to take a step back and try to get really good data regarding what’s best – how best to diagnose and treat this group so we do more good than harm. Much more good than harm. Minimal harm and a lot of benefit is the goal of all healthcare.”

Unfortunately, the picture painted by the Swedish journalists is one of minimal benefit for children and a lot of buck-passing by doctors.

Leo’s back, shoulder and hips are constantly aching. His distraught mother says: “A 15-year-old shouldn’t have to deal with that. His bones shouldn’t look that way. A healthy skeleton that’s been destroyed by this medicine.”