Should psychiatrists revise their ‘Goldwater Rule’?

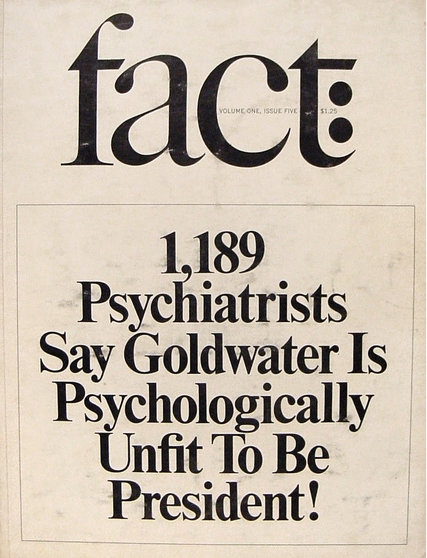

American psychiatrists are ethically barred from commenting on the mental health of public figures under the so-called Goldwater Rule.

This criterion, which was adopted by the American Psychiatric Association in 1973, states that “it is unethical for a psychiatrist to offer a professional opinion unless he or she has conducted an examination and has been granted proper authorization for such a statement.”

In 2016 and 2017, a number of psychiatrists faced criticism for violating the Goldwater rule, as they claimed that Presdent Donald Trump had serious mental health issues even though they had never examined him.

Bandy X. Lee, a psychiatrist at Yale University, even published a book of essays by 27 psychiatrists, psychologists, and other mental health experts, The Dangerous Case of Donald Trump. They argued that, in Trump’s case, their moral and civic “duty to warn” America superseded professional neutrality.

Is it time to revise the Goldwater Rule?

Writing in Psychiatric Times, three psychiatrists argue that their colleagues need to participate in public debates. They believe that the Goldwater Rule can be maintained but needs a few tweaks because the media environment has changed so much.

The public is bombarded with mountains of information and opinions on a minute-by-minute basis. Unfortunately, much of the material is inaccurate and even harmful. Misinformation and disinformation regarding mental health and mental illness now abound. Who better to provide accurate and helpful knowledge than mental health experts, whose education, training, knowledge, and expertise can be brought to bear on the prevailing public and social issues of the day?

They offer five possible amendments to the Goldwater Rule. Basically they would allow a psychiatrist to comment in the broadest possible terms. He could say that the behaviour displayed by a politician is broadly consistent with a particular mental illlness, but also a number of other disorders.

They give the following example:

Senator Brown” has been observed, on several occasions, walking unsteadily in public and slurring his speech. There are persistent rumors in the lay press that Senator Brown has a drinking problem. A mental health professional is asked by a television news reporter, “Doctor, can you comment on Senator Brown’s abnormal behavior? Do you think he is an alcoholic? Is he fit to do his job?”

Inappropriate response: “Based on his unsteady gait and slurred speech, it is my professional judgment that Senator Brown likely has a serious drinking problem. This could well impair his ability to carry out his functions as a senator and lead to some dangerous behaviors.”

Appropriate response: “I have not evaluated Senator Brown, so I do not want to speculate on his condition or mental capabilities. Certainly, when someone shows gait instability and slurred speech, I would want to have that person evaluated medically. The problem could be some type of intoxication, involving alcohol or some other substance. But these reported behaviors could also be consistent with a metabolic or neurologic disorder of some sort. For example, hypoglycemia and various postictal (ie, following a seizure) states may be mistaken for alcohol intoxication.8 Whether the senator’s condition—whatever it may be—would impair his ability to carry out his duties or cause dangerous behaviors would require a careful neuropsychiatric examination.”