Corruptio optimi pessima, o medice?

The behaviour of Nazi doctors is universally accepted as a touchstone of bioethics. In the current issue of the Journal of Medical Ethics, a medical student asks whether doctors are actually more likely than other professions to be moral monsters.

Sooner or later, one side in an internet debate will invoke the Nazis to prove a point. Whereupon his opponent will triumphantly deride this as a logical fallacy called Godwin’s Law – that the first person to say “Nazi” in a debate has lost.

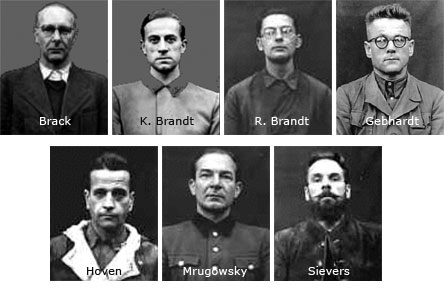

However, the Nuremberg Doctors’ Trial is universally accepted as a touchstone of bioethics. Of 23 German doctors who were tried after World War II, nine were imprisoned for participating in atrocities and seven were hanged. In the current issue of the Journal of Medical Ethics, a medical student asks whether doctors are actually more likely than other professions to be moral monsters. After all, by 1945 half of all German doctors had joined the Nazi Party and 7% of all German doctors were members of the SS, compared to 1% of the general population. The British doctor Harold Shipman was one of the worst of all serial killers – at least 218 people died under his care before he was arrested in 1998.

Alessandra Colaianni, of Johns Hopkins Medical School, asks the unsettling question: “Is there something inherent in being a physician that promotes a transition from healer to murderer?” Some recent situations in the United States suggest that this is possible: allegations of euthanasia in the wake of Hurricane Katrina, torture of Guantanamo detainees, and the participation of doctors in capital punishment. Colaianni suggests that there are illuminating parallels between medical training and the work of doctors in Auschwitz.

Socialisation and hierarchy: doctors are pressured to conform to group norms, often with techniques like “Sleep deprivation, heightened stress levels and fear of failure”. Ambition: just as Nazi doctors participated in the T4 euthanasia program to advance their careers, today’s doctors are pressured to succeed even at the risk of losing their integrity. Doctors have a “licence to sin” which can easily be perverted: some “actions are allowed when they are performed by physicians, but are the stuff of horror films and criminal cases when non-licensed personnel attempt them.”

Detachment was also a characteristic of Nazi doctors. They could select prisoners by day and dine with their colleagues by night: “the medical profession requires unflappability in the face of things that others would consider disgusting, horrific, or otherwise overwhelming”.

Colaianni concludes that medical students need to realise how vulnerable they are to being seduced by the special privileges of their profession. “It is for this reason that a solid grounding in principles of ethics, individualism and human rights is so crucial for physicians and others in positions of power or trust.” ~ Journal of Medical Ethics, early on-line, May 3

Michael Cook

https://www.bioedge.org/images/2008images/dachau1.png

medical ethics

Nazi doctors

- Queensland legalises ‘assisted dying’ - September 19, 2021

- Is abortion a global public health emergency? - April 11, 2021

- Dutch doctors cleared to euthanise dementia patients who have advance directives - November 22, 2020