French novelist Michel Houellebecq won’t submit to euthanasia wave

The controversial writer says that supporters distort the meaning of words

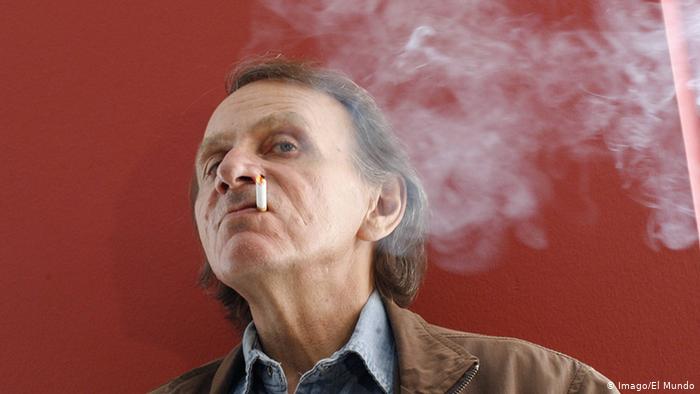

Michel Houellebecq (above, with cigarette) is France’s most acclaimed living novelist, a perennial nominee for the Nobel Prize in Literature, and a provocateur extraordinaire. Contradictory adjectives blanket his name like particolored Post-It notes: brilliant, pornographic, brutally honest, Islamophobic, violent, humanist, nihilistic, repugnant, bold, Marxist, reactionary, etc, etc.

He must also be one of the most outspoken opponents of euthanasia in France. In a recent article in Le Figaro (republished in UnHerd), he explains himself, in his characteristically bitter and poetic language:

Partisans of euthanasia like to gargle on words whose meanings they distort to such an extent that they should no longer even have the right to utter them. In the case of “compassion,” the lie is palpable. When it comes to “dignity”, things are more insidious. We have seriously deviated from the Kantian definition of dignity by substituting, little by little, the physical being for the moral one (and maybe even denying the very notion of a moral being), substituting the human capacity for action with a shallower, more animal, concept of good health — turned into a sort of pre-condition of all possibility of human dignity, even maybe its only true meaning.

Put in this way, I have rarely had the impression that I have manifested extraordinary dignity at any time in my life; and I do not have the impression that this is likely to improve. I am going to end up losing my hair and my teeth. My lungs will be reduced to shreds. I will become steadily more or less impotent, more or less incapable, perhaps incontinent and possibly even blind. Once a certain stage of degradation has been reached, I will inevitably end up telling myself (and I will be lucky if it is not someone else pointing it out to me) that I no longer have any dignity.

But as he points out, physical dignity is not what keeps us going. It is the feeling that we are loved. The source of dignity is relational — not autonomy, but being loved by other people. He goes on to say:

Well, so what? If that is dignity, one can very well do without it. On the other hand, everyone more or less needs to feel themselves necessary or loved; and, failing that, esteemed—even in my case admired. It is true that can also be lost; but one cannot do much about that; others play in this respect the determining role. And I can easily imagine myself asking to die in the hope that others reply: “Oh no, no. Please stay with us a little longer.” That would be very much my style. And I admit this without the slightest shame. The conclusion, I am afraid, is inescapable: I am a human-being utterly devoid of all dignity.

Houellebecq is a kind of social catastrophist. His famous novel Soumission (Submission) is a vision of France transformed by years lived under Sharia Islamic law. He goes on to say that euthanasia is a kind of civilisational test:

The honour of a civilisation is not exactly nothing. But really something else is at stake; from the anthropological point of view. It is a question of life and death. And on this point I am going to have to be very explicit: when a country — a society, a civilisation — gets to the point of legalising euthanasia, it loses in my eyes all right to respect. It becomes henceforth not only legitimate, but desirable, to destroy it; so that something else — another country, another society, another civilisation — might have a chance to arise.

Michael Cook is editor of BioEdge

- How long can you put off seeing the doctor because of lockdowns? - December 3, 2021

- House of Lords debates assisted suicide—again - October 28, 2021

- Spanish government tries to restrict conscientious objection - October 28, 2021