‘I feel your pain!’ Really?

Why do Americans suffer more nowadays?

“I feel your pain,” Bill Clinton told an AIDS activist in the 1992 presidential campaign. Well, he probably didn’t. Pain is notoriously subjective and hard to measure. Some patients take the dentist’s drill without an anaesthetic; others would rather die.

In the 19th and early 20th Centuries doctors speculated why some groups were more sensitive. One popular theory was that less civilised groups were both less sensitive to pain and more expressive when they experienced it. Doctors contrasted stalwart, stoic Britons with degenerate, weeping dark-skinned people.

A contrasting theory was that civilisation was making people soft. The father of modern neurology, Silas Weir Mitchell, wrote in 1892 that “in our process of being civilized we have won, I suspect, intensified capacity to suffer. The savage does not feel pain as we do: nor as we examine the descending scale of life do animals seem to have the acuteness of pain-sense at which we have arrived.”

Today the opioid epidemic makes the study of differential rates of pain more urgent than it ever was. Current research seems to indicate that Americans in lower socio-economic groups experience more pain.

“If you’re looking at all pain – mild, moderate and severe combined – you do see a difference across socioeconomic groups. And other studies have shown that,” says University at Buffalo medical sociologist Hanna Grol-Prokopczyk. “But if you look at the most severe pain, which happens to be the pain most associated with disability and death, then the socioeconomically disadvantaged are much, much more likely to experience it.”

It’s also relevant in the debate over assisted suicide. Unbearable pain, or even the prospect of unbearable pain, is often regarded as sufficient reason to ask a doctor’s help in committing suicide.

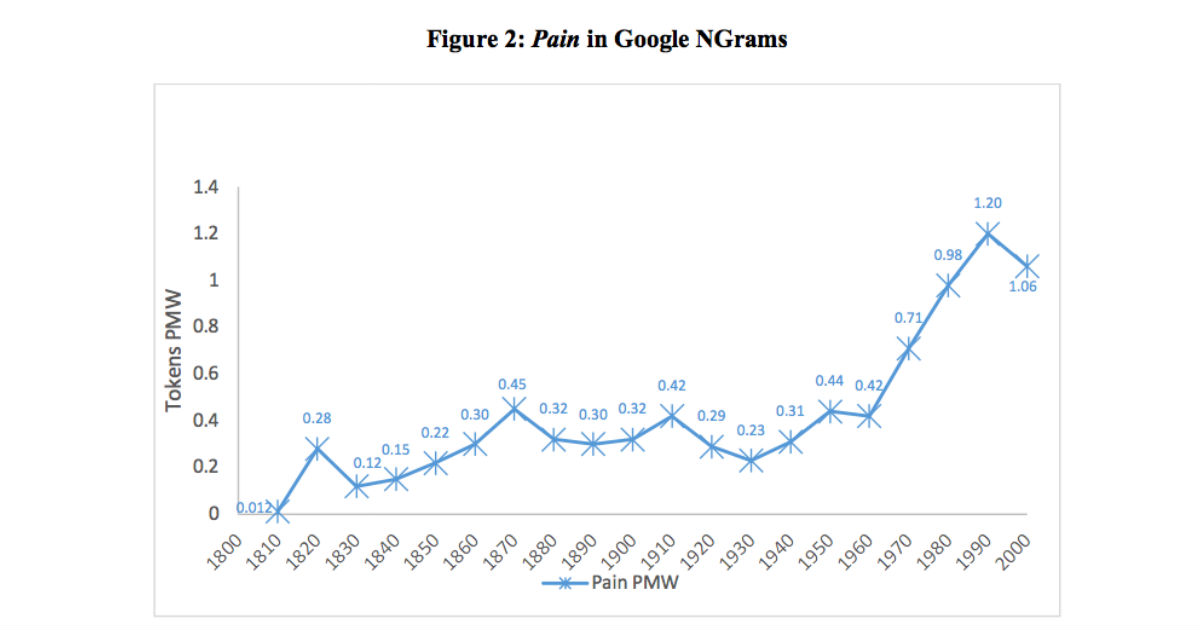

Coming at this issue from a completely different perspective, linguistics expert David Johnson, of Kennesaw State University, in Georgia, found another answer in word usage. Writing in the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion he charted the frequency of the words pain and hurt since the year 1800 in four linguistic databases: Google Books Corpus, Corpus of Contemporary American English, Corpus of Historical American English, and Time Magazine Corpus. What he found was a sharp increase in “pain language” in American English since the 1960s.

Why? It is impossible to propose a definitive answer based on linguistic data, but Johnson’s investigation points at some intriguing lines of inquiry. His theory is that “this growth parallels the era when language related to the divine was in sharp decline”. In other words, a much greater willingness to talk about pain is correlated to a decrease in religious motivation for enduring pain.

… increasing American secularism plays a significant role. After all, the dilemma of the co- existence of pain and a good God is an eternal problem. To suffer in silence is lauded as the appropriate Christian response to pain. And there is a long Christian tradition of promoting suffering in silence …

But with the increasing secularization in 20th and 21st century American society, notions of Christian stoic piety evaporated; thus, people discuss their pain more. And why not? If suffering in silence is not meritorious nor does it assist in religious redemption, then, like [the Greek mythological figure] Philoctetes, sufferers should complain all they want. If for no other reason, it might make them feel better. Interestingly, the data presented above does show an increase in pain, particularly since the 1960s in American English, which coincides with the same era when language related to the divine was in sharp decline.

Creative commons

https://www.bioedge.org/images/2008images/FB_pain_Ngram.jpg

god

pain

religion

- How long can you put off seeing the doctor because of lockdowns? - December 3, 2021

- House of Lords debates assisted suicide—again - October 28, 2021

- Spanish government tries to restrict conscientious objection - October 28, 2021