Why a London museum should return the stolen bones of an Irish giant

Some 250 years after his body was taken, it’s time to accord Charles Byrne the respectful burial he deserves

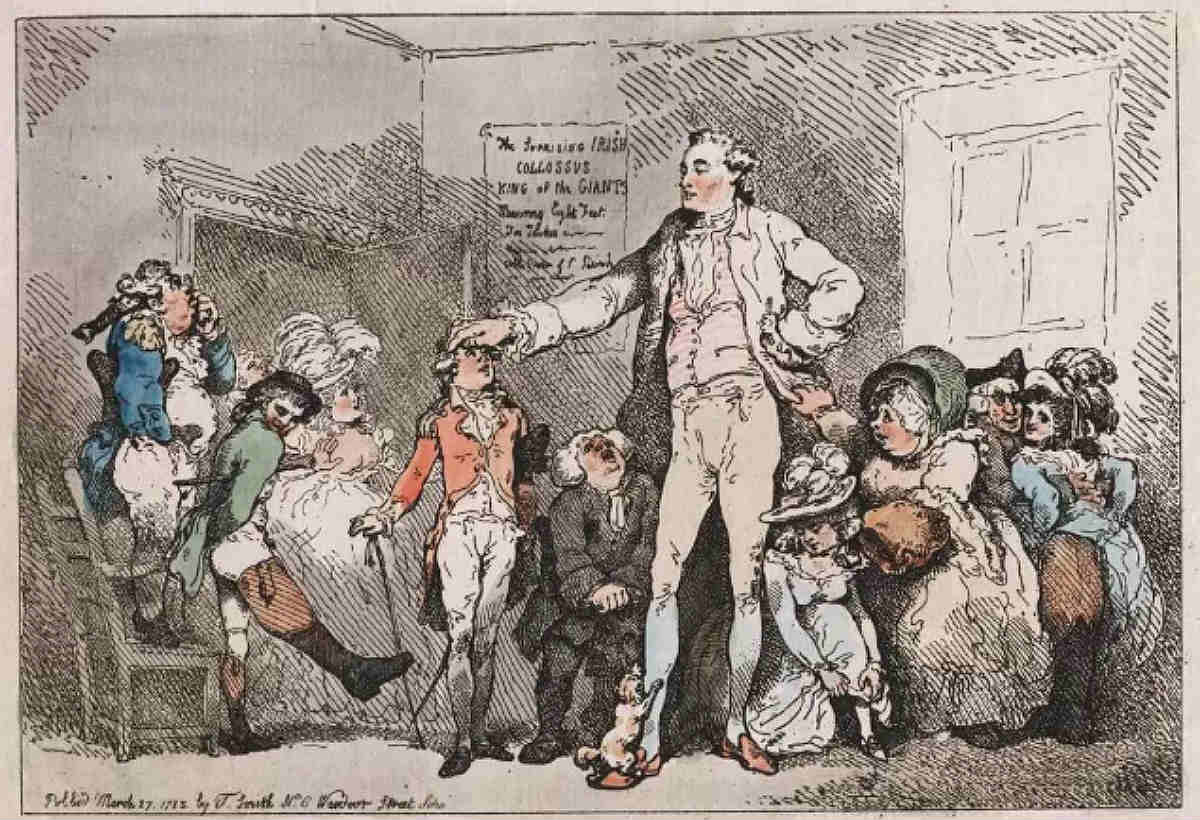

It has all the hallmarks of a Mary Shelley-style Gothic melodrama. A young man, born in 18th-century Ireland with a condition that makes him a “giant”, turns himself into a freakshow curiosity and becomes a celebrated figure in Georgian London. Then he comes to the notice of an eminent Scots surgeon who becomes obsessed with his potential value as a medical exhibit. The young man is left devastated when he is pickpocketed of his life savings, contracts TB and succumbs to an untimely death at just 22. Enter the evil bodysnatchers who remove his body before it can be buried at sea.

Except this story really happened. Fast forward to the present – and add in the London museum that refuses to give up the giant’s remains for the burial he had wished for – and the novel practically writes itself. In fact, historical novelist Hilary Mantel did just that in her 1998 novel The Giant, O'Brien.

The recently published research of human geographer Catherine Nash does an excellent job of untangling this complex story. Born in County Derry in 1761, Charles Byrne suffered from acromegalic gigantism, a condition causing him to grow to an astonishing height – his remains reveal he was around 2.3 metres tall.

After a successful run as a society curiosity, he fell into despair following the theft of all his savings. With depression, TB and his worsening condition hastening his end, a dying Byrne told friends to weigh down his coffin and bury him at sea, afraid his body would be stolen for medical research. Under the June 6 and 7 entry of its June 1783 issue, the Londonderry Journal published the following paragraph:

Sunday died, in Cockspur Street, Charing Cross, Byrne, the famous Irish giant, whose death is reported to have been precipitated by excessive drinking, to which he was always addicted, but more particularly since his late loss of £700.

When the sea burial occurred at Margate on the south coast of England, surgeon-anatomist John Hunter had already bribed an undertaker to switch the corpse en route for dead weight and bring him the body. Afterwards, Hunter put Byrne’s skeleton on display.

Today, that skeleton remains on display in London’s Hunterian Museum, named after the surgeon himself. But as the museum undergoes a period of closure for refurbishment, campaigners are calling for the release of the remains for burial. The Hunterian trustees have refused, arguing that the skeleton has important educational and research value.

Twist in a tall tale

My academic research with Len Doyal sparked much of the present campaign. I have since researched the legality of the museum’s treatment of Byrne’s skeleton, finding that while its trustees arguably are treating the remains unethically, they are not behaving unlawfully.

So what does Nash’s new work add to Byrne’s case? Unravelling this 250-year-old saga, Nash’s commentary highlights certain unpublicised connections that have assisted the Hunterian in hanging on to Byrne’s remains.

Nash posits that Ronan McCloskey’s 2011 BBC documentary Charles Byrne – the Irish Giant, was in fact “timed to closely follow, but not pre-empt” the publication of an important research paper involving scientific analysis of Byrne’s DNA, led by endocrinologist Marta Korbonits.

Korbonits has worked closely with the museum in her research, and does not object to the display of Byrne’s bones. Nash notes that the endocrinologist collaborated with McCloskey in making his documentary, pointing out that Korbonits acknowledges her work was “facilitated by the Hunterian Museum who gave permission for genetic material to be extracted from one of Byrne’s teeth”.

This genetic work found that Byrne had a specific gene mutation and shares genetic ancestry with people living with acromegalic gigantism in Northern Ireland today. In line with medical privacy ethics, the identities of these people were not revealed. Only one person has come forward publicly from the genetic ancestors to express views on the subject – Brendan Holland, who supports the museum’s display of Byrne’s skeleton.

But when the appropriateness of the display was challenged by the campaign, Samuel Alberti, then the director of the Hunterian Museum, fashioned an artificial narrative claiming that several of Byrne’s ancestors supported it:

Benefits of medical research conducted on Byrne’s skeleton include … the identification of shared genes between Byrne and living communities. Among these are individuals who live with the same condition, who have requested that the skeleton should remain on display.

Nash finds that Holland had a long-term relationship with the department of endocrinology at Barts hospital in London, where Korbonits led her DNA research into Byrne’s genetic material. Having been treated there as a young man, Holland, Nash suggests, had fashioned himself as a “spokesperson” for the Hunterian position on retaining the exhibit that relates to his own condition. I would suggest Holland is too closely involved with the Hunterian to be considered someone speaking independently on the matter.

She also highlights that Holland collaborated with McCloskey’s documentary, and that in 2013, “anonymised extracts from a presentation that Holland delivered at a museum event were incorporated into the [Byrne] exhibition panel entitled Giant Genes”. Again, this arguably compromises Holland’s voice as an independent advocate of the Byrne display.

The voices opposing the museum’s actions are getting louder and louder, and include the likes of Mantel as well as several Irish politicians successfully lobbied by campaigner Michael Brennan, and even John Hunter’s biographer Wendy Moore.

![]() Now that the Hunterian has closed for refurbishment, the trustees have some thinking time. Do they respect the big Irishman’s last wishes, or continue to display his remains in a museum built as a memorial to the very man who stole them? Some 250 years after his body was taken, it’s time to accord Charles Byrne the respectful burial he deserves.

Now that the Hunterian has closed for refurbishment, the trustees have some thinking time. Do they respect the big Irishman’s last wishes, or continue to display his remains in a museum built as a memorial to the very man who stole them? Some 250 years after his body was taken, it’s time to accord Charles Byrne the respectful burial he deserves.

Thomas L Muinzer, Lecturer in Environmental Law and Public Law, University of Stirling. This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Copyright

https://www.bioedge.org/images/2008images/FB_charles_byrne.jpg

burial

respect for cadavers

respect for dead

- How long can you put off seeing the doctor because of lockdowns? - December 3, 2021

- House of Lords debates assisted suicide—again - October 28, 2021

- Spanish government tries to restrict conscientious objection - October 28, 2021